“The master said

I set my heart on the Way, base myself on virtue, lean upon benevolence for support and take my recreation in the arts.”

[Analects VII 6]

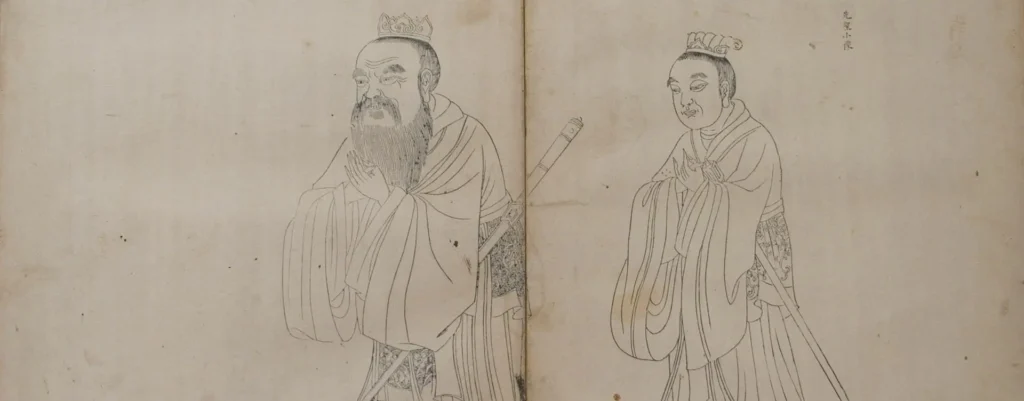

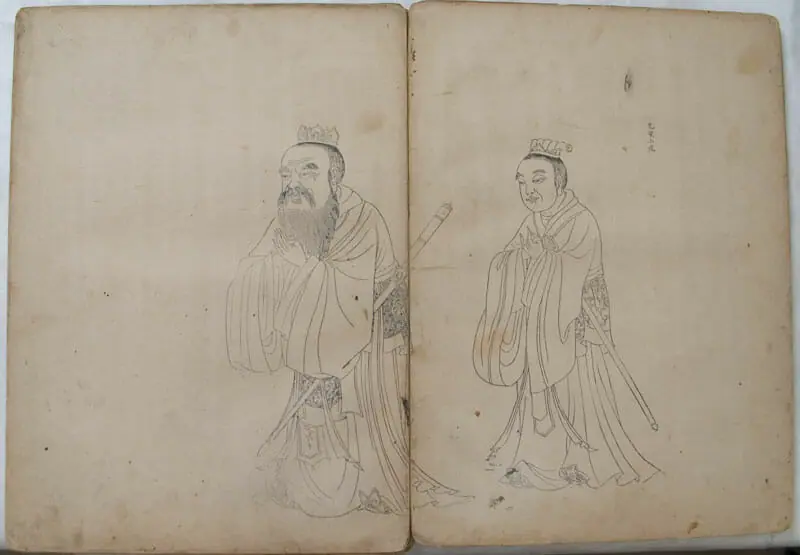

Born in the fifth century BC, Confucius’ 2,570th birthday was celebrated in 2019. Across the world there are temples and institutes established in his name. His great work, The Analects, has been translated into all major languages, and thousands of books have been written on his teachings.

We will be looking in this article at the work of Confucius rather than at Confucianism, which includes the work of Confucius’ followers, Mencius, Xunzi and other Neo-Confucian policy-makers in East Asia, as well as contemporary scholars.

Inspite of the global influence of Confucius, there is a trend (especially in the West) of associating Confucius’ teachings with rigid moral codes of behaviour and systems of education that are undesirable and even detrimental to learning.1Such systems of learning are characterised as reliant upon the use of rote learning, memorisation without understanding, didactic teaching, neglect of critical and higher order thinking, and suppression of individual creativity.

In forthcoming articles, I hope to go some way to debunking this view of Confucius’ ethics as dogmatic and of his pedagogy as obsolete and deleterious.

This is not, however, to jump on the other popular bandwagon, which champions Confucius as a management guru. Reducing Confucius’ teachings to a set of skills, strategies and techniques for managers, shorn of their philosophical underpinnings is every bit as limited, simplistic and ultimately misleading as believing that his work amounts to nothing more than a set of strict educational and moral rules.

What Confucius has to offer is both more than and very different from these conceptions. We get some notion of the breadth and depth of his life’s work from the quote from the Analects that is at the start of this article.

As with Socrates, his counterpart and contemporary in the Greek world, Confucius’ teachings are always given in the context of an engagement with a particular person in a specific situation. This at least is true of Confucius’ central text, the Analects, with which we will be exclusively concerned.2I will take it as given that all the chapters of the Analects represent Confucius’ teachings and that they form one complete text. There is some debate on this topic, but I agree with readers who believe that the consistency of terminology and philosophical and religious thinking incline us strongly in this direction. The text is not a systematic treatise but a series of conversations between Confucius and his disciples, rich with idioms and aphorisms, yet often brief and highly compact. The persons involved, the context and the specific issue at hand are all pertinent to gaining an understanding of Confucius’ replies and reactions, and can rarely be ignored without some loss of meaning.

What we know of Confucius’ life is mainly drawn from two sources: The Zuozhuan, a commentary on the historical record The Spring and Autumn Annals, both chronicling the history of the Spring and Autumn period (722–468 BC), and the Records of the Historian written by court historian Sima Qian during the Han dynasty.

It is said that Confucius was descended from a noble family, but that his family had been forced to relocate before Confucius’ birth, with a resulting loss of status. Confucius’ father died when he was young and he was brought up in modest circumstances by his mother. We know that he was married and had at least one son and daughter. We know that he had both military experience and skill and that, as a scholar, he committed himself to learning at an early age.

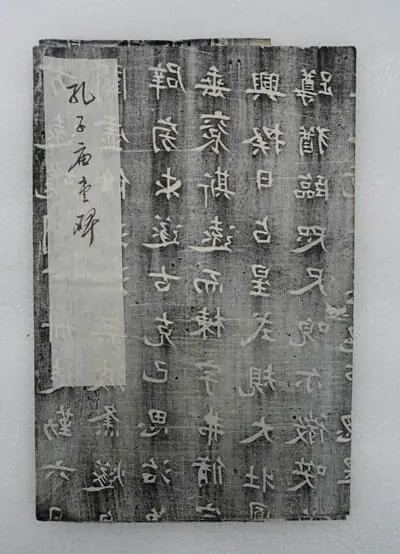

The name used in the West, “Confucius” was coined by Jesuit missionaries who went to China in the sixteenth century. It is a Latinised version of Kong Fuzi or Kongzi, meaning “Master Kong”. Confucius’ real name was Kong Qiu, “Kong” being the family name and “Qiu” his given name. In the Analects he is simply addressed as Fuzi, master.

Confucius grew up during the second half of the Zhou dynasty in a time called the Spring and Autumn period (722–468 BC). It was an epoch rife with social and political turmoil, with rulers of different states vying for power and control. Through his teachings and his service in government, Confucius attempted to restore order and harmony. He did not believe in the practice of harsh rule by law and punishment, and attempted to replace this with the rule by virtue (De). His guide for this was the historical figure of the Duke of Zhou, who opposed “rule by fear” and instead advocated “rule by example”.3The Duke of Zhou was Confucius’ hero. Although little is known of the Duke, he is held to be responsible for a key pillar of the cultural foundations of China: the “Mandate of Heaven”. This said that Heaven approved the earthly rulers on condition that, or for as long as, the wellbeing of the people was at the forefront of their minds. The Duke’s nephew, King Cheng, was the emperor but was too young to wield power and so the Duke was made regent. He is famed for having followed the “Mandate of Heaven” by handing over power to his nephew when the correct time came, rather than holding on to it at all costs, as is often the case with rulers of all nations. (Analects III.14, VIII.20, VIII.21, IX.5).

In his fifties, Confucius worked as Minister of Public Works, and later as Minister of Crime in the state of Lu. He famously left this latter position after a few years, disappointed with the behaviour of court officials and the Duke of Lu. He resigned himself to travelling between states, accompanied by his loyal band of disciples, repeatedly attempting and failing to fill official positions, again often leaving disappointed with behaviour of officials. Returning to Lu after fourteen years, Confucius spent his remaining years teaching. During this time he edited and revised a number of classical texts, including the Ya and Song sections of the Book of Songs, and the Book of Documents, demonstrating his scholarship and interest in both the arts and history. He is believed to have died at the age of 72.

In the next article on Confucius we will be looking at key aspects of his teachings in the Analects.